Al Capone

Al Capone is America's best-known gangster and the single greatest symbol of the collapse of law and order in the United States during the 1920s Prohibition era. Capone had a leading role in the illegal activities that lent Chicago its reputation as a lawless city.

Al Capone is America's best-known gangster and the single greatest symbol of the collapse of law and order in the United States during the 1920s Prohibition era. Capone had a leading role in the illegal activities that lent Chicago its reputation as a lawless city.

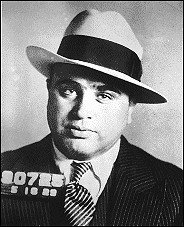

Al Capone's mug shot, 1931.

Capone was born on January 17, 1899, in Brooklyn, New York. Baptized "Alphonsus Capone," he grew up in a rough neighborhood and was a member of two "kid gangs," the Brooklyn Rippers and the Forty Thieves Juniors. Although he was bright, Capone quit school in the sixth grade at age fourteen. Between scams he was a clerk in a candy store, a pinboy in a bowling alley, and a cutter in a bookbindery. He became part of the notorious Five Points gang in Manhattan and worked in gangster Frankie Yale's Brooklyn dive, the Harvard Inn, as a bouncer and bartender. While working at the Inn, Capone received his infamous facial scars and the resulting nickname "Scar face" when he insulted a patron and was attacked by her brother.

In 1918, Capone met an Irish girl named Mary "Mae" Coughlin at a dance. On December 4, 1918, Mae gave birth to their son, Albert "Sonny" Francis. Capone and Mae married that year on December 30.

Al Capone

Capone's first arrest was on a disorderly conduct charge while he was working for Yale. He also murdered two men while in New York, early testimony to his willingness to kill. In accordance with gangland etiquette, no one admitted to hearing or seeing a thing so Capone was never tried for the murders. After Capone hospitalized a rival gang member, Yale sent him to Chicago to wait until things cooled off. Capone arrived in Chicago in 1919 and moved his family into a house at 7244 South Prairie Avenue.

Capone's first arrest was on a disorderly conduct charge while he was working for Yale. He also murdered two men while in New York, early testimony to his willingness to kill. In accordance with gangland etiquette, no one admitted to hearing or seeing a thing so Capone was never tried for the murders. After Capone hospitalized a rival gang member, Yale sent him to Chicago to wait until things cooled off. Capone arrived in Chicago in 1919 and moved his family into a house at 7244 South Prairie Avenue.

The unpretentious Capone home at 7244 South

Prairie Avenue, far from Chicago's Loop and

Capone's business headquarters.

Capone went to work for Yale's old mentor, John Torrid. Torrid saw Capone's potential, his combination of physical strength and intelligence, and encouraged his port�ig�i. Soon Capone was helping Torrid manage his bootlegging business. By mid-1922 Capone ranked as Trio�s number two men and eventually became a full partner in the saloons, gambling houses, and brothels.

Al Capone

When Torrid was shot by rival gang members and consequently decided to leave Chicago, Capone inherited the "outfit" and became boss. The outfit's men liked, trusted, and obeyed Capone, calling him "The Big Fellow." He quickly proved that he was even better at organization than Torrid, syndicating and expanding the cities vice industry between 1925 and 1930. Capone controlled speakeasies, bookie joints, gambling houses, brothels, horse and race tracks, nightclubs, distilleries and breweries at a reported income of $100,000,000 a year. He even acquired a sizable interest in the largest cleaning and dyeing plant chain in Chicago.

Although he had been doing business with Capone, the corrupt Chicago mayor William "Big Bill" Hale Thompson, Jr. decided that Capone was bad for his political image. Thompson hired a new police chief to run Capone out of Chicago. When Capone looked for a new place to live, he quickly discovered that he was unpopular in much of the country. He finally bought an estate at 93 Palm Island, Florida in 1928.

Political cartoon depicting Chicago's growing reputation for violence.

Al Capone

Attempts on Capone's life were never successful. He had an extensive spy network in Chicago, from newspaper boys to policemen, so that any plots were quickly discovered. Capone, on the other hand, was skillful at isolating and killing his enemies when they became too powerful. A typical Capone murder consisted of men renting an apartment across the street from the victim's residence and gunning him down when he stepped outside. The operations were quick and complete and Capone always had an alibi.

The Tribune headline after the St.

Valentine's Day Massacre of 1929.

Capone's most notorious killing was the St. Valentine's Day Massacre. On February 14, 1929, four Capone men entered a garage at 2122 N. Clark Street. The building was the main liquor headquarters of bootlegger George "Bugs" Moran's North Side gang. Because two of Capone's men were dressed as police, the seven men in the garage thought it was a police raid. As a result, they dropped their guns and put their hands against the wall. Using two shotguns and two machine guns, the Capone men fired more than 150 bullets into the victims. Six of the seven killed were members of Moran's gang; the seventh was an unlucky friend. Moran, probably the real target, was across the street when Capone's men arrived and stayed away when he saw the police uniforms. As usual, Capone had an alibi; he was in Florida during the massacre.

Capone masterminded the 1929 St. Valentine's Day

Massacre, which left seven men dead, but was in

Florida when it happened. All but one of the victims

were members of rival "Bugs" Moran's gang.

Although Capone ordered dozens of deaths and even killed with his own hands, he often treated people fairly and generously. He was equally known for his violent temper and for his strong sense of loyalty and honor. He was the first to open soup kitchens after the 1929 stock market crash and he ordered merchants to give clothes and food to the needy at his expense.

A line outside Capone's "Free Lunch" restaurant, Al Capone

Capone had headquarters in Chicago proper in the Four Deuces at 2222 S. Wabash, the Metropole Hotel at 2300 S. Michigan Avenue, and the Lexington Hotel at 2135 S. Michigan Avenue. He expanded into the suburbs, sometimes using terror as in Forest View, which became known as "Caponeville." Sometimes he simply bribed public officials and the police as in Cicero. He established suburban headquarters in Cicero's Anton Hotel at 4835 W. 22nd Street and in the Hawthorne Hotel at 4823 22nd Street. He pretended to be an antique dealer and a doctor to front his headquarters.

Capone maintained a five-room suite and four

guest rooms at the Metropole Hotel (2300 S.

Michigan Avenue). The hotel served as his base

of operations until 1928.

Because of gangland's traditional refusal to prosecute, Capone was never tried for most of his crimes. He was arrested in 1926 for killing three people, but spent only one night in jail because there was insufficient evidence to connect him with the murders. When Capone finally served his first prison time in May of 1929, it was simply for carrying a gun. In 1930, at the peak of his power, Capone headed Chicago's new list of the twenty-eight worst criminals and became the city's "Public Enemy Number One."

The popular belief in the 1920s and 30s was that illegal gambling earnings were not taxable income. However, the 1927 Sullivan ruling claimed that illegal profits were in fact taxable. The government wanted to indict Capone for income tax evasion, Capone never filed an income tax return, owned nothing in his own name, and never made a declaration of assets or income. He did all his business through front men so that he was anonymous when it came to income. Frank Wilson from the IRS's Special Intelligence Unit was assigned to focus on Capone. Wilson accidentally found a cash receipts ledger that not only showed the operation's net profits for a gambling house, but also contained Capone's name; it was a record of Capone's income. Later Capone's own tax lawyer Lawrence P. Mattingly admitted in a letter to the government that Capone had an income. Wilson's ledger, Mattingly's letter, and the coercion of witnesses were the main evidence used to convict Capone.